Theme Discussion

Started in 2016, this urban public space design competition attracts proposals every year from throughout Japan and the rest of the world. Through an open review process and publication in the pages of this magazine, the competition has helped to disseminate the forms of urban and public space that will populate our future cities. The theme for this year’s fourth installment of the competition is “Public Space in the Year 20XX.” In addition to Takayuki Kishii (head of the selection committee), Ryue Nishizawa, and Tadao Kamei, we invited two new review panel members, Takeshi Kito and Eriko Ozaki, to discuss the topic of future cities and the nature of public space. (The Editors)

The future of urban public space

First of all, I would like to ask all the review panel members what their views are of this year’s theme, “Public Space in the Year 20XX.”

Tadao Kamei (hereafter, Kamei): This is the fourth year that we are holding this urban public space design competition. At the time, we were inspired to launch the competition because of a casual conversation that I had with Kishii-sensei: we remarked that architectural designers, including recent students, do not really discuss the topic of cities, and wondered if it was because their interest in cities as such had dwindled. Cities are, quite naturally, important to architecture. If you look at the works that were submitted to our open call in the past, you can get a real sense of how perspectives for thinking about cities have taken root, year by year. The term “public space” itself has also come to be used more often everywhere you go. In Tokyo, as well, there are new urban planning initiatives currently underway in districts like Shinjuku and Shibuya. In these large scale developments, you can also see many successful examples where public space has been integrated into them, such as open plazas at the base of buildings and rooftop gardens. Every year, we have review panel members for this competition who are active in fields other than architecture. The reason for this is that we believe it is indispensable to have perspectives from people who are involved in a variety of domains outside architecture when it comes to thinking about the notion of public space. With this in mind, we have invited Takeshi Kito and Eriko Ozaki to take part this year. I look forward to seeing what kinds of discussions will unfold together with Takayuki Kishii and Ryue Nishizawa, both of whom have been involved with the competition since the first installment.

Takayuki Kishii (hereafter, Kishii): When thinking about public space in cities, we need to first understand the fact that the land that is managed by the government — which includes everything from roads, rivers, and parks to amenities like community centers and libraries — makes up about 20 to 40%. These are built and established in accordance with government-stipulated rules in the Road Law and River Law, for instance. In Koshigaya Lake Town, which I was involved in planning, for example, we sought to develop the urban areas in addition to converting a retention basin into a recreational space for water lovers that is open to the public. All this would not have been possible without an understanding of the legal regulations and systems in the background that are not visible on the surface. Unfortunately, such foundational things are not currently being taught in today’s architectural education. I personally feel that one of the problems lies here.

The meaning of the word “public” has also shifted along with the times. In Japan, too, examples of interactive placemaking, public-private partnerships, and area management are increasing year by year. We have gone from a rather narrow definition of public space as seen in so-called public amenities managed by the government, to an era where members of the public take it into their own hands to manage and run spaces that everyone can use. Looking abroad, there is currently a very active movement to embrace public transportation: light rail transit systems that evolved out of trams and streetcars have started running again in cities all across Europe. Even in automobile-centric America, Transit Oriented Development (TOD) has demonstrated success in San Francisco and Denver. In addition, with advances in information and communication technologies, the thinking that underlies Mobility as a Service (MaaS) has started to attract attention as a new concept for “movement” based on seamless connections, which understands movement via all means of transportation as a single service. If regulations and systems shift in response to this sort of trend, I am sure that the nature of public space will also evolve.

I believe the theme for this year is thinking about architecture and cities from the perspective of the notion of public space for a new era. Some might come up with proposals with concrete images of cities and places in mind, while others may approach the theme from a conceptual standpoint. Whatever the case may be, I would like all of us to ponder deeply the frameworks that would allow us to bring these proposals to life. On the other hand, I also think that it is important to imbue outstanding frameworks with forms that are appropriate to them.

In short, if the meaning of the word “public” shifts, systems and frameworks will also evolve in response. Nishizawa-san, which aspects of this year’s competition did you pay particular attention to?

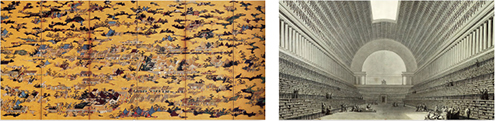

Right: Etienne Louis Boullée’s Deuxième projet pour la Bibliothèque du Roi (Second Project for the Royal Library).

Left: Uesugi Rakuchu Rakugai Zubyobu

Ryue Nishizawa (hereafter, Nishizawa): I feel that the things that express a Japanese sense of public space quite well are scenes from village festivals, for example, or narrow back alleys in cities. I’d like everyone to take a look at this as an example that is easy to understand: the Uesugi Rakuchu Rakugai Zubyobu decorative folding screen, a National Treasure, that depicts the ancient capital of Kyoto and its surroundings (top left of this page). There are several things I find interesting in terms of how this work depicts Japanese public space, so please allow me to explain them. First of all, the painting depicts Rakuchu Rakugai — in other words, the inside and outside of Kyoto — but in fact it is impossible to tell where the “inside” or “outside” of the city begins and ends. There is no distinction between the interior and exterior of the city: the buildings, too, are such that their insides and outsides are continuous. The second thing pertains to how clouds and greenery are scattered throughout the entire space: the natural and the artificial are all intermingled. The third point is that there is no center to this painting. In terms of how this work is drawn, it uses axonometric projection to depict a world in which there is no apparent difference between center and periphery. Thanks to this method of projection, it seems as if the Imperial Palace, the samurai residences, merchants and craftsmen, farmers, and all the other people are going about their merry lives regardless of class.

The other work that I would like to show here is Etienne Louis Boullée’s Deuxième projet pour la Bibliothèque du Roi (Second Project for the Royal Library, top right). I love this particular drawing: for me, it is one of the most beautiful and powerful drawings in the world of architecture. Its beauty and power stems from how perspective is deployed here. While this work by Boullée was made around the same time as the Rakuchu Rakugai painting, the differences between them could not be starker. What is impressive about this drawing is its centrality. An order and rank among all things emerges as a result of this perspective. What is more, while the things in the center are accurately depicted, the picture gets more distorted the further to the edges you go, creating a sense of hierarchy between the center and the margin. This is a monotheistic world. The interesting thing about perspective is that in order to draw according to it, it is necessary to fix not just a vanishing point that represents divinity, but also a standing point where the self is supposed to be located. In other words, this is a world that cannot be depicted without determining the (boundless) existence of a one true god, as well as one’s own perspective, or an individual mode of thinking. Axonometric projection, on the other hand, does not require either a vanishing or a standing point. Accordingly, the result is a world without a center, or a world with multiple centers, where any place can potentially assume the role of that center: a pantheistic world, in other words. In an axonometric projection, both the center and edges of the picture are distorted in the same proportions. In a sense, it is a world where everything is equivalent. People of both high and low social status drink together: this image of public space that exists as an extension of a village festival that creates a lively bustle in both the homes and streets is clearly depicted according to this technique called axonometric projection. Just as how Western and Eastern conceptions of public space diverge to such a degree, the ways in which public space is depicted effectively present a certain worldview, in my opinion. The single term “public space” is saddled with the burden of history and culture.

There are, no doubt, particular images of public space that are appropriate to each city. On this point, I would like to ask Kito-san his opinion.

Takeshi Kito (hereafter, Kito): I think the question of data is unavoidable if we are thinking about a near-future situation in the year 20XX. Moving forward, the link between cyberspace and physical space is going to change dramatically. The Mobility as a Service (MaaS) that Kishii-san was just talking about is in a similar situation. We are seeing the advent of a world in which data circulates seamlessly and in real time, within a system where cyberspace and physical space become one.

Also — and there is some overlap here with what Nishizawa-san was discussing — we are currently seeing some unprecedented changes in the nature of social governance. Traditional systems of governance are predicated on closed ecosystems: centralized organizations maintain a certain static order, by having the state govern its citizens vertically, for instance. The presumption of this closedness is a fiction, however. The real world is an open-ended system: what is necessary is to create order within this fluid dynamic. In my opinion, the future of society ought to be one where various stakeholders relate to each other on a horizontal basis while a dynamic state of order is created across them. In that case, what should we do to transform the social systems and rules created according to the aforementioned traditional models into the fluid models that we should be seeing? Personally, I define “architecture” as the relationship between the elements that make up all of these systems, and “architects” as those who are tasked with designing them. At a time when we are witnessing a major turning point in terms of social structures, I believe that this role is one that will become increasingly important. Actually, I am currently involved as a member of a committee of experts for the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Cabinet Office, working on social governance models for the future and the design of protocols that can implement them in a dynamic way.

For this year’s competition, it may be ideal to have proposals that hint at the possibility of a new “architecture” of this sort.

Ozaki-san, you are currently implementing various urban initiatives in the city of Nagareyama. What are your thoughts on cities and public space, in the context of your activities?

Eriko Ozaki (hereafter, Ozaki): The population of the city of Nagareyama, Chiba Prefecture, where I live, has increased by 40,000 over the 14 year period from 2005-2019. Currently, it is a city of about 190,000. As of 2018, Nagareyama ranks number 8 across Japan in terms of people who are moving there. With an increasing population, a city is expected to have more places with a public character to them. In my case, the main focus of our activities is on creating these public spaces ourselves instead of relying on the government, and running them as sustainable businesses, even if they are on a small scale. We are mainly involved in running entrepreneurship schools for women, daycare centers for school-going children, and satellite offices. Apart from these businesses, I am also engaged in activities aimed at producing city council members from among mothers who are raising children in Nagareyama. I think it is important to raise the motivation (independence) of local residents so that interesting projects will steadily emerge out of a particular city. In my view, this will help to draw companies, money, and people to the city.

Personally, I feel that all public goods ought to be created for the sake of the children who will support the future of Japan. To this end, the most cutting-edge styles of working, most advanced technologies, and interesting adults should always be at the side of these children. In concrete terms, our approach consists in thinking about what it would be like to incorporate all of these functions into the schools where the children are, instead of having adults go into the city to work. Currently, we are working with the top brass of local government bodies and struggling to create a precedent that can serve as a model. Personally, I conceive of public space by taking children as a topic, but I am also looking forward to seeing what kinds of topics will emerge from those who are submitting proposals to this competition.

Nishizawa: I think it’s a great idea to have adults go to the schools. The question of the necessity of foreign languages sometimes comes up, but once you’ve lived together with people who speak a foreign language, you understand each other, no questions asked. Before the advent of modern education, children were raised right in the midst of adult society, in villages or temples. In that sense, what Ozaki-san is describing could be said to be both futuristic and historical at the same time.

Shifts in boundaries

Kamei: As I was listening to what everyone was saying, it struck me that one of the keywords for this year’s competition might be “boundaries.” Over the past few years, the speed at which information is coming and going has really accelerated. The physical circulation of people has also increased. The rise in inbound tourism, for example, is not limited to Japan. We’ve reached a point where you are unable to get in to see the popular tourist spots abroad if you don’t make a reservation online in advance. I think this is directly linked to just how much information is circulating. Kito-san was just making a reference to the relationship between the physical and the cyber. I think this is an expression of exactly how seamless those boundaries have become. So I think this idea of ambiguous boundaries is a common theme, whether it’s Nishizawa-san talking about urban images of Japan as seen in folding screen paintings, or Kishii-san talking about MaaS.

Kito: I think one way to define the “public” is in terms of a complementary set taken from the whole, excluding the parts that are private. Then it might also be possible to think about public space by taking one’s starting point from the question of how to define this “whole,” and what is “private.”

The boundary between private and public is a subject that has been pondered in a variety of fields. In the financial domain, for instance, open APIs (application programming interfaces) have allowed secure data linkages between banks and external contractors. We have moved away from a conventional closed system of individual banks, and entered an era of connections between open-ended systems. I think there is also the question of how we can expand on and develop this approach: how can these processes be adopted not just in finance, but also in our cities?

Kishii: In terms of the discussion of private and public, our movements, actions, and purchasing history, for instance, are already being used as personal data. In a sense, they have become entirely public. Today, those who have access to bundles of this sort of data hold the power: personally, I am very interested to see how this situation will evolve in the future.

Kito: In addition to the actual gathering of data, it is important to think about all the frameworks through which this data circulates. That is where the greatest power lies, in my opinion. For instance, when thinking about driverless cars, it doesn’t just begin and end with the production of the cars: it is also necessary to think about traffic rules and infrastructural development in terms of roads. It’s only when all of these necessary components are in place that a society where this is implemented can become a reality. Similarly, cities do not begin and end when the physical urban landscape has been created. It is also important to design the entire surrounding environment, including the rules that allow these cities to be used, or the mindsets of people, for example. I think it would be really interesting to have some proposals with such a perspective.

Public space for whom?

So it seems as if the question of how to design frameworks is going to be an important one. Ozaki-san, you are involved in actually creating physical spaces like daycare centers for school-going children and satellite offices. Is there any advice you might be able to offer from the frontline, so to speak?

Ozaki: If you pay too much attention to communality and publicness, your business won’t be able to survive, and you end up with places that nobody makes use of. If you seek to create something that will satisfy older men, children, and foreigners alike, however, you run the risk of ending up only with bland, inoffensive ideas. Insofar as I am going to be reviewing them, I’d like to see some ideas that really stand out. In addition to making the target audience clearer, I think it would be ideal if we could interpret the word “public” more freely.

Kamei: In the end, you need money to create these sorts of public spaces. We also need perspectives on how money can be generated from these spaces, and how we can make them sustainable.

Kishii: In terms of trends concerning the kinds of proposals that we receive, there have been very few that considered these issues to that degree. I think it would be great if our participants went one step further in how they take these issues into consideration.

Nishizawa: Architectural departments are places where we think about a variety of issues related to buildings. I think there is a tendency here to think about architecture as some sort of standalone entity that is detached from its surroundings. Take the case of Japan: the basic principle is one plot with one building on it, surrounded by the boundary lines of the site. Looking at this kind of Japanese urban space, you can see that we are in a situation where buildings are being thought about in isolation, separately from the city. I think this is one of the reasons that interest in cities as such is dwindling. In addition to being a structure within a particular plot of land, a building is part of the street, which belongs to everyone, in a certain sense. I would like everyone to be aware of this fact when thinking about the notion of public space.

Kito: Discussions of plots of land and buildings tend to revolve around the issue of ownership. When it comes to data and cyberspace, however, access and control rights become more important than the issue of ownership as such. Perhaps it will also be necessary to think carefully about the boundary between public and private in terms other than those of ownership.

Ozaki: There are so many potential topics: I am looking very much forward to what gets proposed. Finally, I would just like to say this: I hope that we don’t lose sight of our original starting point — the perspective of the consumer or end user. I don’t mean to imply that God is in the details, but I really think that the question of whether one assumes the viewpoint of those who will actually make use of these spaces is an extremely important one.

Kamei: This is something that really strikes a chord with us, as well. I really enjoyed sharing this time with everyone, and hearing interesting perspectives from you all. Thank you very much.

July 18, 2019, at the head office of Nikken Sekkei

Compiled by the editorial department of Shinkenchiku

Nikken Sekkei

The Japanese term kokyo kukan (public space) tends to conjure up images of spaces that have been publicly developed by the government. Currently, however, many public spaces are also being constructed on sites that are privately owned. For Tokyo Midtown Hibiya (issue 1805), the urban planning for which was handled by our company, we earmarked a number of roads in Chiyoda Ward to be abandoned, replacing them with an open square and designing what we call the “Hibiya Step Square,” which spans an area of some 4,000m2. In addition to making roads pedestrian-only, this project also involved creating a barrier-free underground network called the “Hibiya Arcade” that serves as a connecting node for two subway lines, seeking to create an urban zone that would boost the navigability of the area in a way that would be more pedestrian friendly. Efforts were also made from an economic perspective to make this area sustainable, by introducing area management initiatives with the participation of government bodies, corporations, and neighborhood associations.

In contrast to the creation of a permanent open plaza at Tokyo Midtown Hibiya, “Park Pack” was a project where we implemented a mobile design for a “park for the future.” This was an idea that was put forth for an event organized by Tokyo Midtown in Roppongi, where we installed four containers that stored a variety of tools for making the open plaza more lively. Depending on the combination of tools deployed, the plaza could become a stage or a cafe, giving rise to a variety of activities.

What sort of public space will be able to impart value to our future cities? At Nikken Sekkei, we look for answers to this question through the design of various kinds of public spaces.

Atsushi Omatsu / Nikken Sekkei

Atsushi Omatsu / Nikken Sekkei

All three photos by Kotaro Imada, Imada Photo Service

Photo provided by Nikken Sekkei

Top: Hibiya Step Plaza, developed as part of Tokyo Midtown Hibiya

Center left: Pedestrian-only road within Hibiya Step Plaza

Center right: Hibiya Arcade

Bottom: View of Park Pack, installed at Tokyo Midtown in Roppongi

Takeshi Kito

I founded a fintech company called Crowd Realty in 2014, running a platform that assumes the functions of an investment bank, which does P2P (peer-to-peer) matching between investors and those seeking to raise funds. At Crowd Realty, we provide services that securitize real estate and raise funds, making it possible for anyone to create a framework equivalent to a REIT (real estate investment trust) online, with complete ease. To take just one example, for a project that involved renovating a Kyoto machiya townhouse and converting it into an accommodation facility, we raised 70.2 million yen from 110 people, which was channeled to the fundraiser’s new business. In this way, I consider the act of designing frameworks and platforms as a contribution to cities and public space in a broad sense.

Top: Business of renovating a machiya townhouse where funds were raised through Crowd Realty

Bottom: Extract from the Crowd Realty website. Anyone can raise funds or make an investment online.

Photo provided by Crowd Realty

Eriko Ozaki

In 2014, I founded Shinsenryoku, a consulting company that supports women who have given birth to their second child in creating work spaces and starting businesses, as well as producing daycare centers for school-going children. In 2016, I started the shared office Trist, attracting companies located in Tokyo to take up residence. There are many women who gave up their jobs after giving birth and starting to raise children in the city of Nagareyama, Chiba Prefecture — myself included. By getting Tokyo-based companies to hire these women and have them work remotely from Trist, commuting times can be shortened, making it possible to work while raising children at the same time. Although I am not an expert on cities or public space, I believe that what Shinsenryoku does is intimately connected to these things. For this competition, too, I would like to review entries from the perspective of the consumer and end user as much as possible.

Top: Working spaces at Trist’s second location. Opened in 2018, this second location was created by local residents, who renovated this space themselves, in a building owned by the city authorities.

Top: Working spaces at Trist’s second location. Opened in 2018, this second location was created by local residents, who renovated this space themselves, in a building owned by the city authorities.

Bottom: Renovation work in progress.

Photo provided by Trist